by Dianna Phelps

When I was growing up my favorite hour each week was the glorious hour I spent at Re-Creations Musicke Shoppe. It was a quirky little place, jam-packed with any and everything you could think of that is related to music. It was literally stuffed wall-to-wall. At first glance you might think you were in an episode of Hoarders but after taking a closer look, you saw sheer magic. Everywhere you looked you could see an instrument and I don’t mean your run-of-the-mill guitars, pianos, horns and drums, although they were there too. I’m talking about instruments like a harpsicord, several hand-made dulcimers, an accordion and my favorite: a washboard. Every week during that holy hour, my brother and I had back-to-back, 30-minute music lessons. When I was either waiting for my lesson to begin or waiting for my brother’s lesson to end, I wandered around the store exploring and taking in all of the exotic and fascinating things my small mind had never seen before. I pretended I knew how to play all of the instruments and daydreamed about a world in which everything seemed possible.

We first began taking music lessons when we were 9 and 10 years old. We had recently moved in with our Grandmother who knew that we both enjoyed learning to play the recorder while attending our previous school. Even more, she knew that keeping us busy and engaged in something we enjoyed would help to ease the transition of our move, so she signed us up for recorder lessons. Enter one Ms. Edith Duhon, the town music teacher.

Ms. Duhon was in her mid to late 50s, rocked the most pristine hair-do consisting of a neat bun with a tightly secured bow fastened directly underneath. She was an anomaly for our small town. She was well-educated, well-travelled, had no children and married late in life. In rural Louisiana that was shocking, unheard of even. I remember being instantly intrigued and smitten by her. She was utterly brilliant, playing to some extent every instrument in her store. Who does that? I surely had never met anyone that talented and I’m not sure I have since.

During one recorder lesson, Ms. Duhon had my brother and I sing a song together with her. She had one good listen and said, “Dianna, you need to find your voice.” What a lovely way of saying I was practically tone deaf. She was like that. She could love you and make you feel valued while simultaneously telling you the cold, hard truth. After a while, I grew bored with recorder and my brother moved on to piano. She suggested I take voice lessons but I opted to stop taking lessons altogether. She didn’t give up though. She would see me when my grandmother would pick my brother up from his lesson and would remind me that I needed to work on finding my voice and she could help me do it. She was very convincing and it didn’t take long for me to begin taking voice lessons. During high school, she would use this same persistence to keep me in lessons when I wanted to quit. Each week I would work up the nerve to tell her I’d planned to stop lessons but before I could get around to it, she’d pull out all of my favorite pieces, make me sing them and I would fall in love with singing all over again. By the time I left my lesson I couldn’t imagine a world in which I didn’t get to sing with her and be in her presence for at least 30 minutes a week.

I could spend a lot of time writing about technical things I learned about music and singing during my lessons but, while those things are important and I’m grateful for having learned them, the best learning that I did during that time has nothing to do with actual music or singing. Ms. Duhon taught me other lessons. Life lessons. She said to me once, “Dianna, I had been to Europe and back three times before I married. You need to know that it’s important for you to have a life of your own before you share it with someone.” Growing up in tiny-town Louisiana, I had never heard those words uttered by anyone. It was a powerful realization that my life could be what I wanted to make it and it didn’t have to look like everyone else’s that surrounded me. Those words were compelling. They felt like freedom and possibility.

Ms. Duhon didn’t just teach music and life-lessons, she exposed me to life through the arts in numerous ways over the course of our time together. She took me to my first ballet. I remember it like it was yesterday. I hated it. But I remember being in awe of how glamorous she was for the event. She wore a dress and a costume jewelry broach and when we ate dinner beforehand at the buffet she pronounced the word boo-fay. She. Was. Everything. She took me to my first opera, Samson and Delilah, which I loved. She also took me to see Handel’s Messiah, which was the first time I remember falling in love with orchestra. These things might seem insignificant to some but these experiences enlarged my worldview exponentially and in ways none of my other life experiences had to that point.

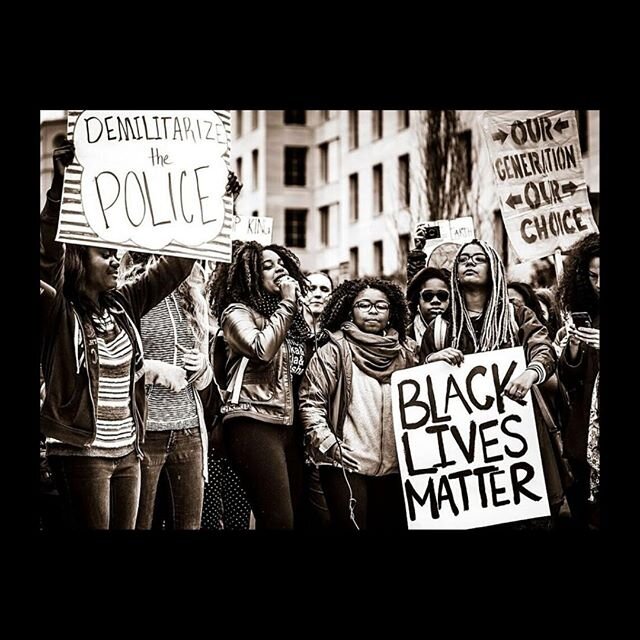

In my case, music lessons didn’t produce a performer or a musician. The totality of my music career consisted of singing at church and in college choir, and even then I had a strong apprehension to solos. For me, music and singing is solely personal; something I have for myself and my enjoyment. Ms. Duhon’s music lessons did help me find my voice and make me a singer but more importantly they instilled a deep, profound love of the arts, which makes my life richer. They excited curiosity in me and made me seek understanding of the world in a new and more diverse way. They gave me a much needed outlet to express my feelings and if you know me, you know I have ALL of the feelings.

On a recent trip to NYC to visit my brother, we were taking a train uptown and began reminiscing about Ms. Duhon and her influence. By the time we reached our stop we were both crying. We were crying because we felt an overwhelming sense of gratitude. We were crying because she was a magnificent human and through relationship and the gift of music, she changed the trajectory of our lives. That isn’t something you take for granted. That’s something that you hold close and sacred. I’m not a musician but what I know with absolute certainty is that the arts are so subtlely and thoroughly woven into my life that the implications are long-lasting and far-reaching in ways I’ve yet to even understand. Thank God and Ms. Duhon for that.

_________________________________

Dianna Phelps is a school-based mental health professional with a proven track record of success in providing evidence-based supports and interventions. Her areas of expertise include School Climate & Culture, Positive Behavior Interventions and Support, Social Emotional Learning, Behavior Intervention & Discipline and Multi-Tiered Systems of Support. Dianna currently lives in Atlanta and works for Fulton County Schools where she coaches teachers under the Disproportionality Project, which is aimed at plugging the school-to-prison pipeline by providing behavior intervention, restorative practices and support services to students in need. Dianna holds a B.S. in Sociology from Southern Nazarene University, a M.A. in Counseling from Louisiana Tech University and has completed post graduate work at Loyola University Chicago in Advanced School-Based Mental Health Practice.